Today’s conversation might piss off a few prophylactic companies (no, I’m not suggesting we buy thumb tacks and go crazy). The question of the day is…how can we get people to procreate?

No, the lingerie and aphrodisiacs aren’t going to save us this time, we’re talking about bigger changes. A good starting point is making having kids easier: lower costs for essentials like housing, electricity, and food. But then you still need those parents to remain part of the workforce. So, the sticking point is childcare.

Affordable childcare might just be the most effective policy to sustain birthrates and keep your workforce intact in the process. Certain industries in the US (like healthcare) and countries (like Scandinavia) have somewhat figured this out, although it can be pricey.

Once you get the childcare piece taken care of, then you need space for these children to play and grow. Take New Zealand for example, they’ve found a way to keep children (and tipsy adults if we’re being honest) busy for hours and hours…

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from Tongariro National Park in New Zealand while I’m doing the Tongariro Northern Circuit, that is mountain Guro in the background, which is and we basically we’ve been going around it the whole time. So why it’s called Tongariro Circuit, not in the whole circuit, I don’t know. Anyway, you might recognize that mountain from Lord of the rings that is Mountain Doom.

So I prefer to call this track the Doom Loop. Anyway, today, taking a question from the Patreon crowd. And that’s specifically if demographics are so core to the success and failure of countries, what are some policies that could be adopted to encourage demographic expansion? Just great question. Quick review. People between 20 and 45 are the ones who are raising kids and spending money and building homes.

That’s where most consumption comes from. People between roughly 45 and 65, the kids have moved out. The house has been paid for, but they’re earning a lot. So the consumption is down, but their income is high. And so they are investing. And that’s where the capital in the tax base comes from, having a balance between those two. Without too many retirees, but enough children to generate the next generation.

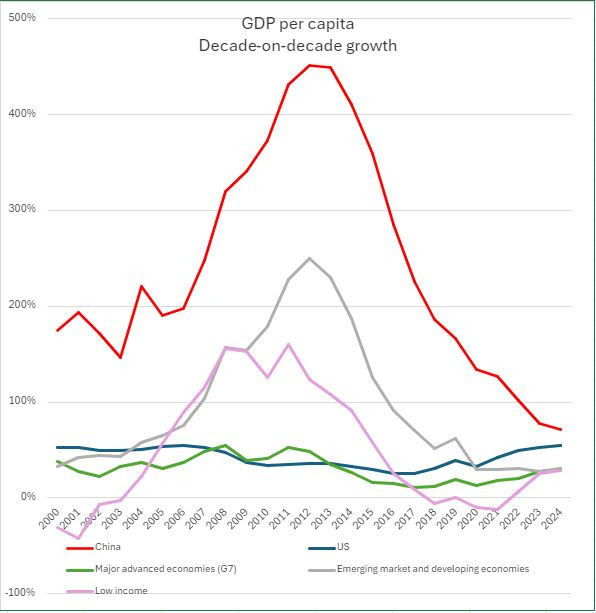

That’s ultimately what you want anyway. In most of the world, that’s not what we have. Birth rates have been declining for so long that most of the advanced world, including China, in that are not just running out of children. That happened 20, 30, 40 years ago. They’re now running out of working age adults. So for many of these countries, it’s too late, but not for everybody.

For New Zealand, France and the United States and the Scandinavian countries, the demographic structures are much younger, and so there’s plenty of chance to rehabilitate. Really, it comes down to one thing. Whether you make it easy to have kids, financially speaking, so low cost of electricity, low cost of land, low cost of food, those are all real impetuses.

And finding ways to manipulate those things is absolutely important. But the biggest thing is making sure that would be parents are able to still make choices. And for that, you need to keep both parents in the work force should they so choose. And so it isn’t so much subsidization or paying people to have kids that rarely works.

Instead, it is making sure that there are abilities, the parents can still work and have kids. And that really comes down to childcare. If you can provide affordable, easily accessible childcare, that’s the single biggest thing you can do to keep the birth rates high, because parents, whether men or women are going to not feel like that, they have to make sacrifices in order to have a family, in the United States.

I would argue that the only place that we get this right is with health care personnel. Because if you’re on call and you have to run into the hospital or the clinic, then your kid has to go somewhere. And so there’s a really robust system in the United States for that, for that specific subsector. But for everyone else, you’re kind of on your own.

If you don’t have a grandparent or an aunt or uncle nearby. The Scandinavians have done this a different way where they just have state subsidized health care for everybody. But that gets really expensive really quickly. Hopefully we can figure out something in between in the United States, before the birthrate drops to low.

Okay. We’re going to finish this one up for menopause. Now, as any parent will tell you, there’s one other thing that you have to have if you’re going to be raising kids in that space and the transition from agrarian to industrialized lifestyles, we all started moving into towns and the ability to banish kids to the outside went down.

So even more than needing childcare, you need the ability to put your kids somewhere. Well, in New Zealand, they’ve got that in spades. Not only is there a lot of green space in the country, but they have gone out and built in every major population center, including all the minor ones. Something really special.