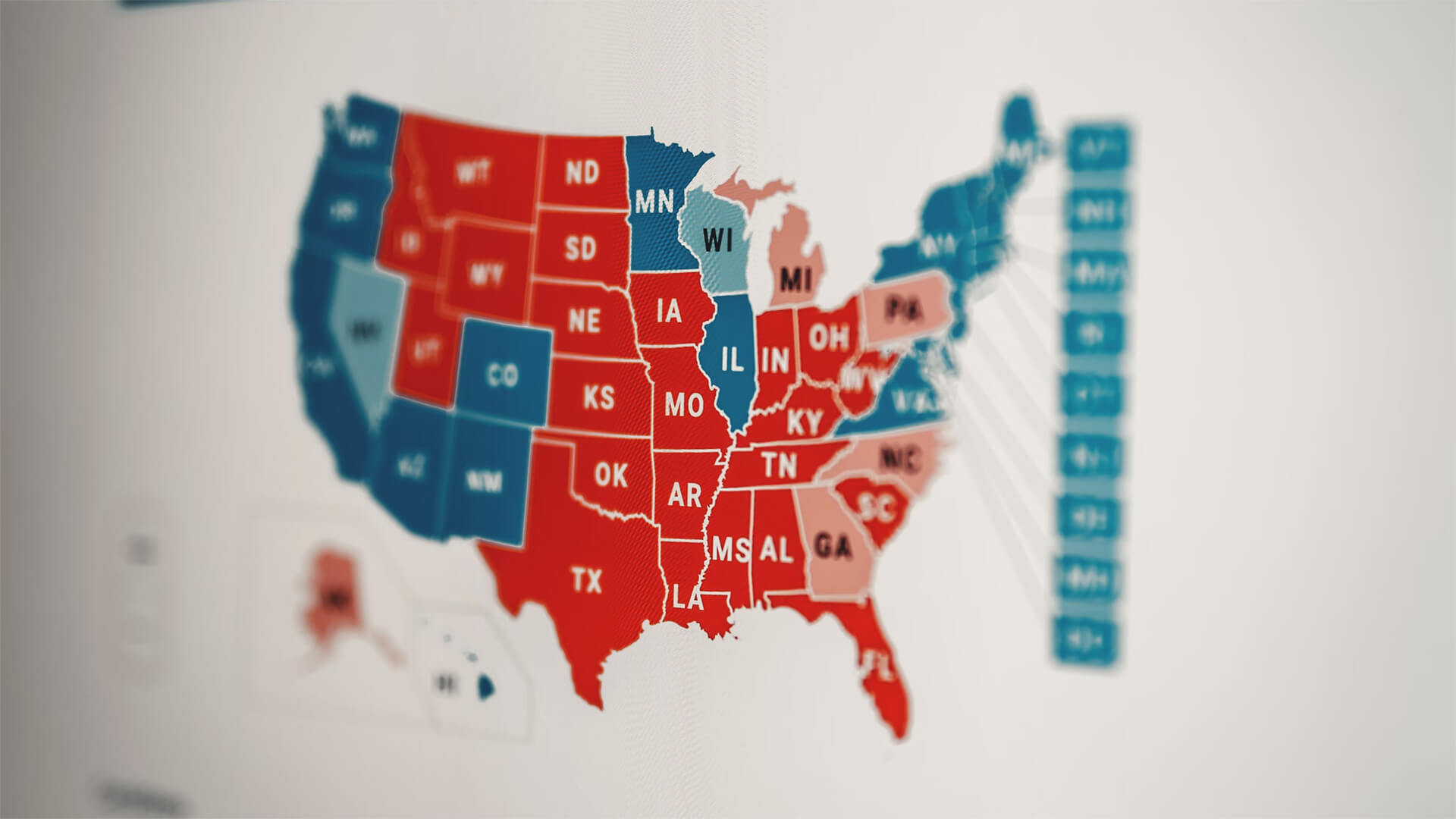

America After the Election: Foreign Policy

Listen, I debated even entertaining an election video for today, but since this question was so good, I just had to record one.

The question is: what aspects of American foreign policy are going to stick with us regardless of who wins the presidential election? The answer is not as eloquent.

I’m sure that not one of you will like what I had to say and that’s fineeeee, because as long as I pissed off everyone, I should be in the clear…and I coincidentally planned an international trip, so enjoy! Muahahahah!

Does Turkey Have the Power to Control Israel’s Future?

Israel has had a lot of eyes on it lately and many are starting to wonder what the future looks like for this small and arid country. Let’s break this down through the lens of deglobalization.

With US involvement and globalization set to decline, Israel could be losing a very valuable partner. Remember that the US has supported Israel with critical resources like food and energy, as well as on the security and military fronts. That leaves some pretty big shoes to fill.

I don’t want to discredit Israel entirely because they have established themselves as a technological power, but that can only take them so far. The main shortcomings being energy, food, and protection. Thankfully there are some viable options out there.

Saudi Arabia and Israel have already begun working together and I would expect that to continue. Turkey, who will take some convincing to enter into a partnership, would be a powerful addition to the team (Turkey is poised to be the regional leader moving forward, thanks to its military and economic power). And then we’ll throw in Egypt to round out the roster.

I don’t want to put too much stress on this, but if Israel can’t figure out its relationship with Turkey…the Israeli future could look bleak.

Here at Zeihan on Geopolitics, our chosen charity partner is MedShare. They provide emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it, so we can be sure that every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence.

For those who would like to donate directly to MedShare or to learn more about their efforts, you can click this link.

Transcript #1

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here. Coming to you from Colorado, well we are two-thirds of the way through our first ten inches of snow for the season. Ooh. Happy election day to everyone. I had considered just letting this pass and just dealing with the crap that’s going to inevitably happen after. But I got a really good question from one of the Patreon crowd members.

So I figured I would take a shot at it, before I leave the country for a couple days. So, the question is this: what aspects of American foreign policy are going to stick with us regardless of who wins the presidential election? Great question. I do not have a great answer. In the world until roughly…

Oh, let’s call it 2012. We had something in the United States, when it came to foreign policy and strategic policy, called the bipartisan consensus. And the idea was that the Soviet Union was bad. Global communism was not a great idea. And the way for the United States to secure its security, as well as its economic well-being, was to build an alliance network that would span the world and pursue a free-trade world,

a globalized world with everyone so that most countries of consequence would have a vested interest in benefiting from participating in the American security agreements rather than going and doing something else. And that gave us NATO and the Japanese and the Korean, the Taiwanese alliances, and all of that, and built the nonaligned world into an economic powerhouse that wasn’t necessarily aligned with the United States, but really wasn’t aligned with anyone else either.

Broadly worked. But then in 2012, we had eight years of a visceral disinterest in governing, by Barack Obama. And then we got Donald Trump and Joe Biden, who were two of the most economically populist presidents we’ve ever had. And over that 16-year period, the bipartisan consensus has withered away. And the party that was responsible for basically writing most of the real policies, the Republican Party, has now

found itself in a different place with the national security conservatives and the business conservatives not really even part of the party architecture any longer.

And there are some factions of the Republican Party that are finding themselves very strangely aligned on some issues with Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. So, to say that security policy is no longer up for grabs in the United States is not paying attention to what’s really going on. What that means is the United States is in a period of flux, not just politically, internally, but internationally.

Now, this is the topic of a lot of my workings,

Starting with The Absent Superpower and The Accidental Superpower ten years ago. But what we’re seeing in the United States is also churning other things, which means that very few of the things that we consider to be normal national security and economic precepts are likely to survive because the institutions of the parties that formed them are themselves up for grabs.

And we’re seeing the leadership of both the Democratic and the Republican Party taking the institutions into a nonfunctional era. They will reform, and we will get to a situation where we can have a meaningful conversation about foreign policy again, but it’s probably not going to be for a few more years. So we’re stuck with what we have.

So let’s start with the Democrats and Kamala Harris. How can I say this without sounding like a complete prick? She’s an empty suit. Kamala Harris’s only job experience before she became vice president was being a prosecutor, which is, you know, better than the last three presidents, but it’s still not a lot. It’s a relatively minor view of anything.

And so when you look at anything she’s going to say about anything, she’s never actually implemented anything. And so you have to take everything with a big block of salt. In her first year as vice president, she was at Joe Biden’s side in every press conference, every summit, every meeting, and it got to the point that Biden’s staff decided that, no, we don’t want her around.

So they gave her a task that they knew she would fail at and gave her no power to carry it out. And that was going down to solve the border. And so, lo and behold, it was a failure. And then they were able to shovel her off to the side for the next two and a half years until it turns out she’s the presidential nominee.

So if you are voting for Kamala Harris, do not fool yourself. You are voting for an unknown, somebody with very limited experience, and who will come into the White House without a circle of people around her who are competent. They’re going to be people she’s picked up, people who are not loyal to her personally, most likely.

And so it really is a crapshoot. And then, of course, we’ve got the Republican side. And I’m going to put aside for the moment most of my feelings on Donald Trump on strategic issues. I would just ask you to look at really any of his interviews or rallies

in the last three weeks, especially the one that was in Michigan two days ago.

The degradation that I saw during the debate with Biden was in full swing, and this guy is just not all there anymore. So even if he does become president, he probably won’t be for very long. Keep in mind that he is older now than Joe Biden was when Joe Biden became president. And the mental fortitude required for the job is immense.

And Trump just doesn’t have it. So don’t kid yourself. If you’re voting for Trump, you’re actually voting for JD Vance. And JD Vance is even more of an empty suit than Kamala Harris. He’s also a bit of a chameleon, which I don’t know if it’s a plus or minus. He wrote a somewhat famous book,

Hillbilly Elegy, a few years ago, and since then, he’s partially repudiated what he said.

And then he said that Donald Trump was a horrible person, should never be president, and was a danger to democracy. And he’s obviously repudiated that. This is a guy who will say anything to get closer to power. And if Trump wins, he will be the next president. So we’ve got two candidates here who both seem to be fairly economically populist, both of which have no experience in the real world,

and no experience in government—very limited, anyway. And that’s what’s on the docket. So any sort of institutional loyalties are weak to none. Any sort of policy experience that might give us an idea of what they might prioritize is negligible. And so any sort of policies that might have consistency, from the last 20 years to the next four, it’s going to be a short list.

The issue with foreign policy in the United States is that most of it is a presidential prerogative, and it’s very rare that Congress has any say in any of it, at least in the formative stages. And so if we don’t know who, institutionally speaking, politically speaking, ethically speaking, the next president is going to be because there’s no track record,

we don’t know what they’re going to prioritize at all, and we don’t know how they would react to any hypothetical scenario because they’ve never had to do it before. The only policies that are an exception, then, are issues where the president has chosen to cede a degree of authority to Congress and lock something in with an act of Congress that limits the president’s room to maneuver. Those sorts of policies will probably stick because it would require an act of Congress to overthrow them.

In the case of the United States, that’s a very short list of things. And most are related to trade, of which by far the most important policy that falls into that bucket is NAFTA. Now

I’ve made no bones about my general dislike of Donald Trump on any number of issues, but what he did with NAFTA 2 renegotiation, I thought, was brilliant because it was the right thing at the right time with the right partner.

Mexico has become our number one trade partner. And if there is a future for the United States economically, outside of being locked into a very dangerous and unequal relationship with China, Mexico will be the core of whatever that happens to be. And so having the hard work done already, and having it be the isolationist right of the United States that did the negotiations, I thought was great.

So no matter who becomes president next, I think NAFTA is fine. And honestly, that is the single most important foreign policy priority the United States has. So at least when it comes to preparing for whatever is next in the world, as the Chinese become more belligerent and as they start to fall apart, as the Ukraine war crescendos and we face the Russian demographic dissolution as the European

fractures because the population there is making it very difficult for them to do anything else.

The most important single piece of our future was done by Donald Trump, and he deserves credit for that. And I don’t think that whoever his successor is—Harris or JD Vance—is going to have the political authority or interest in overturning that. So, you know, hurray. Now, with that said, I have now probably thoroughly pissed off everybody on both sides.

You should go vote. And you should know that by the time you’re seeing this video, I’m already out of the country, so have a good one.

Transcript #2

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here, coming to you from the coast of South Carolina. Several of you have written in on our Patreon forum with questions about what the future of Israel will be, especially as the world de-globalizes. Well, a little background, and then we’ll go into it.

So, number one: Israel is not a big place. We’re talking about a country that’s roughly the size of New Jersey, in a large neighborhood that is pretty arid and not exactly full of friends. Yes, Israel has built a surprisingly dynamic society with an amazing level of technological acumen, but it didn’t do it alone. The question is whether it can sustain itself; it’s basically a de facto sponsorship of the United States from the beginning. And while, for example, its missile defenses are impressive, the real ones—the ones that intercept the ballistic missiles, the arrows—have never functioned without American participation in terms of targeting, tracking, and even, you know, firing.

So, by far the most capable state of the region, but the PA isn’t exactly high. Here’s a country that imports the vast majority—over 80%—of its energy. And despite all the talk, a kibbutz is something like three-quarters of its food as well. So it’s in kind of a pickle. It requires foreign sponsorship for security and it requires access to economies outside of the region for its energy and its food. You remove the United States as the security guarantor, or you remove globalization, and this should, in theory, be one of those countries that, without a radical change of affairs, is simply going to dry up and blow away.

Now, I don’t think that is Israel’s future because a few things are going to change, some of which already have. One of the things that so frustrates the United States about Israel is it acts on its own. It has agency. When you are so much more technically capable and have so much more reach than your neighbors, you have some options. And the Israelis often exercise that. They often engage in military and paramilitary operations that are directly opposed to U.S. interests. And because of that, the Israelis have this view that no ally is worth forever. If push comes to shove, you do what you feel you need to do. And if it happens to piss off the person who ensures you get fed and the lights come on and the missiles get shot down, well, that’s so be it.

They know that at some point down the road they’re going to have to do things differently. And while they probably can’t do it on their own, that doesn’t mean that they can’t find a new friend. So, the question is, who are the candidates?

Well, in terms of energy, I would argue that they’ve already found that one. Starting over 15 years ago, the Israelis basically built a de facto alliance with Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia would provide them with some intel on Iran and some energy. And in exchange, the Israelis would provide the Saudis with backdoor access to American weapons systems that the Americans were willing to sell to Saudi Arabia, along with the training that was necessary so they could use them. In addition, anything that involves Iran, the two of them will operate pretty closely.

Now, this doesn’t mean they get along on everything. Obviously, when it comes to the Palestinians, there are still some fine details to work out. But the two of them get on pretty well behind the scenes and publicly spout a lot. But behind the scenes, they’re actually getting along great; they’re reasonable friends. Agriculture is easier. There are a lot more countries in the region that provide food surpluses, most notably in Europe. So it’s not like the Israelis need access to the globalized system to keep the food flowing.

But when it comes to security, that basically tells you where they’re going to get their food. Every country in the Middle East is in the process of wondering when the United States will pull back and, if so, who they should go to. And none of the options are particularly good if you’re an Arab. If you consider that the French and the Brits and the Turks have all had colonial empires in the region, no one really wants to go back to that day. But if you’re Israeli, you’ve got some options because the Israelis were never really a traditional colony; it was formed by the Zionist movement in the aftermath of World War II.

Partnering up with France, or Britain, or in my opinion, Turkey, is something that can be done with a minimum of cultural pain. Of the three, the most likely candidate will be Turkey—not because it’s the closest cultural cousin; it’s the opposite. But if Turkey is not a friend, then Turkey will most likely be an enemy. And having an alliance with someone against your local foe puts you really at the mercy of your ally. But if the Israelis can find a way to bury the hatchet with the Turks, then you take the largest economy and military in the area, with the most projection-based economy and military in the region, and you get a very powerful pairing.

That’s going to be pretty easy to justify joining. So I think the future of this region is likely to be Turkish-led, to a degree Israeli-managed, Saudi-fueled. And those three will have no problem bringing in Egypt as a big bulwark partner in North Africa. That quad is likely to be the power center for this region in a post-American system. And they have everything that all of them need—energy, security, naval access, food, and a really good network of intelligence systems.

I know a lot of you are going to say, “Wait a minute, doesn’t the Turkish government hate Israel right now?” Yes. I didn’t suggest any of this was going to be easy. The issue is that the Turkish government can protect Israel from, say, France or Britain, but France or Britain can’t really protect Israel from Turkey. So there’s really not a lot of strategic choice here. You know, if you’re Saudi Arabia, the idea of reaching out to a distant power like Japan or China makes a degree of sense. But for Israel, the potential foe is near and present. So if Israel cannot find a successful way to get along with Turkey, then Israel will vanish.

This is a region that is actually pretty easy for the Turks to get at. They’re not too far away. They only have to punch through Lebanon, and Lebanon is not really going to fight back. Not to mention you’re going to talk about a really meaningful blockade that would starve Israel of food and energy as well. Far better to find a way to get in bed with the Turks than the other way around.

So again, never said this would be easy. Never said there wasn’t a lot of work to do.