If you’ve been around since July, you might remember me talking about Russia targeting Ukrainian agriculture instead of the power grid. If you want a little refresher, just click here:

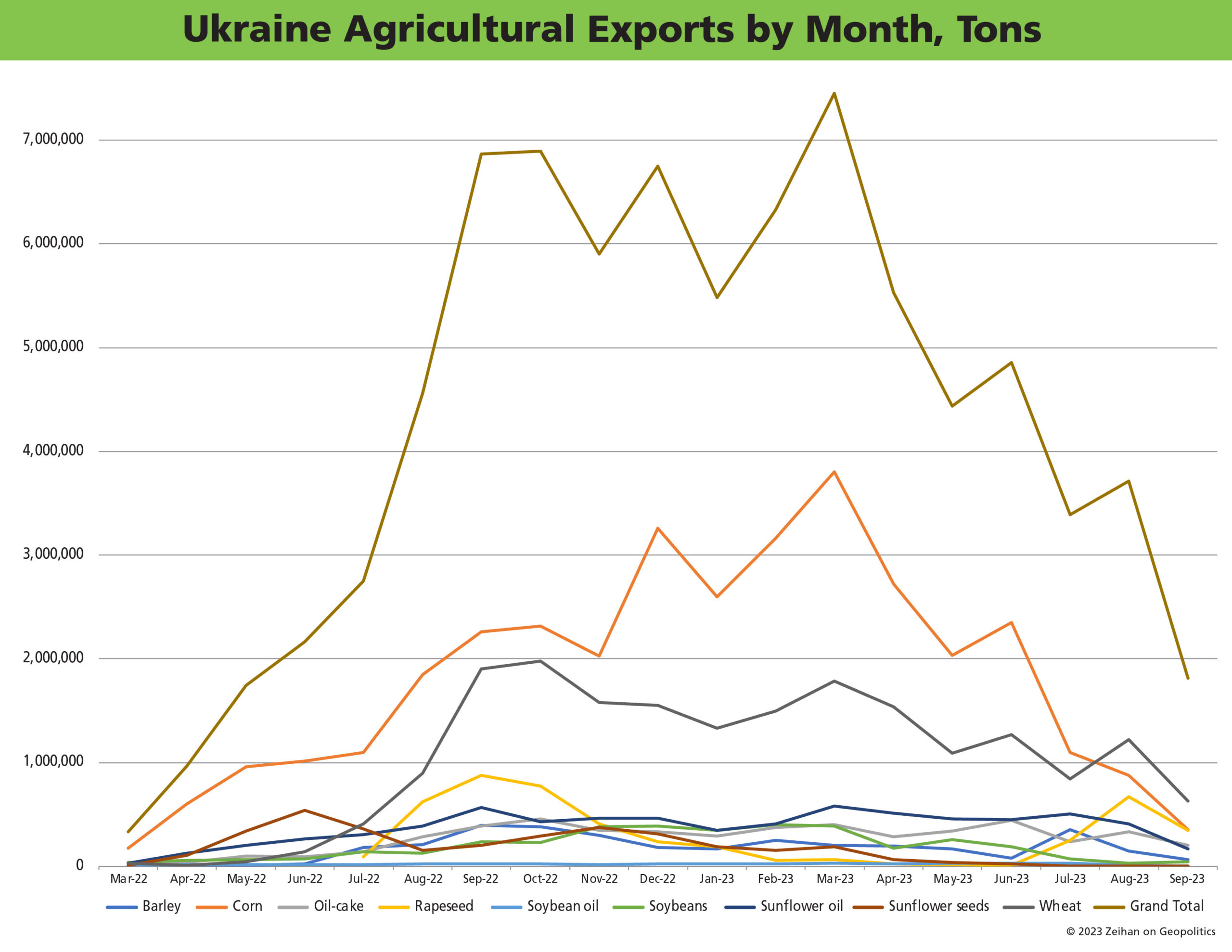

As of September, Putin has sufficiently disrupted Ukraine’s grain exports and overall agricultural sector. Meanwhile, the Russians were bolstering their wheat exports, so global supply has held steady, and prices are still down.

Don’t rely on this Russian grain, though, because new sea conflicts, impacts on shipping routes and an unpredictable climate could change everything at the drop of a hat. The best course of action would be to help Ukraine develop better rail infrastructure and grain transport options.

As the temps begin to shift, we will see the Russians change up their strategy once again. They will transition from attacking Ukrainian agricultural infrastructure back to targeting the power grid…but just because the Russian’s focus has shifted, doesn’t mean grain markets will be stable.

Here at Zeihan On Geopolitics we select a single charity to sponsor. We have two criteria:

First, we look across the world and use our skill sets to identify where the needs are most acute. Second, we look for an institution with preexisting networks for both materials gathering and aid distribution. That way we know every cent of our donation is not simply going directly to where help is needed most, but our donations serve as a force multiplier for a system already in existence. Then we give what we can.

Today, our chosen charity is a group called Medshare, which provides emergency medical services to communities in need, with a very heavy emphasis on locations facing acute crises. Medshare operates right in the thick of it. Until future notice, every cent we earn from every book we sell in every format through every retailer is going to Medshare’s Ukraine fund.

And then there’s you.

Our newsletters and videologues are not only free, they will always be free. We also will never share your contact information with anyone. All we ask is that if you find one of our releases in any way useful, that you make a donation to Medshare. Over one third of Ukraine’s pre-war population has either been forced from their homes, kidnapped and shipped to Russia, or is trying to survive in occupied lands. This is our way to help who we can. Please, join us.

Transcript

Hey everybody. Peter Zeihan here coming to you from Colorado today. The topic is going to be the next phase of the war in Ukraine and from an economic point of view. For those of you who’ve been watching for a while, you know that last winter the Russians went out of their way to hit the power grid in Ukraine wherever and whenever they could, because that was the way they could generate the most casualties and have the most political impact on decisions in Kiev.

And then in about May, once it had warmed up enough that you didn’t necessarily need heating in Ukraine, they switched targets to the agricultural supply chain system with a very, very heavy emphasis on the infrastructure that collects and especially exports the grain take it out. Things like grain silos and ports first in places like Odessa, and then later moving on to the Danube River Delta, which is where the Ukrainians and tried to get the stuff out.

In this, the Ukrainians have kind of faced a triple bind. Number one, they import most of the materials that are necessary, like fertilizer, in order to grow crops in the first place. Number two, there isn’t a lot of storage in Ukraine that was available because of last year’s efforts in the war. Most of the storage was full completely.

So the Ukrainians were focusing on getting that out so they could make room for this year’s harvest. And in some degrees, there has been failure there. And this stuff has nowhere to go because number three, almost 80% of this maybe even a little bit more, goes up by water, primarily through the Odessa region. And with that kind of off line, the only other option is to rail it out.

And that means you have a limited number of rail cars. You have to ship it through other countries that are already grain exporters like Bulgaria, Romania and Poland, who don’t like the idea of that stuff being dumped on their market. So most of them have barred Ukraine from having terminal arrivals for their grain and you have to keep on going.

So for every kilometer you have to go further. That’s a kilometer that that railcar has to be committed. So all in all, you’re talking about over an 80%, nearly a 90% reduction in Ukraine’s ability to get the stuff out. And now that a lot of these ports on the Danube have been damaged, there’s just no place to put the stuff from this year’s harvest.

So from the Russian point of view, mission accomplished. And now they’re switching targets. This past week, the week of the 18th of September, they’ve started switching targets again because we’re now getting into fall and they’re going after the power grid again. And over the course of the next month, I would expect that general shift to be almost complete.

They’ve destroyed the Ukrainians ability to play in international grain markets any in any meaningful way. And now they’re going to have the power grid to cause mass casualties again there. So definitely, you know, the Russians have absolutely won this round. The only way that the rest of the world might be able to help is to massively, massively expand the rail connections between Ukraine and their neighbors.

And then the next line of countries beyond. It’s not enough just to get the stuff to say, Poland or Romania. You’ve got to get it on to the water. And that means you also build out the lifting infrastructure for transferring something from rail onto a ship, because these countries were already grain exporters. That stuff is already used to capacity.

You can basically need to double the entire thing. Normally you would expect something like this to be really bad for grain prices are good, I guess. Depends on your point of view. Send them up. But miracle of miracles. The Russians have had a bumper harvest so they have increased their wheat exports by over a third and that by itself is nearly enough to compensate for all the Ukrainian grain that has left the market.

So wheat prices are actually down. Now, I am not a grain trader and I’m not trying to give you anybody price recommendations, but just a couple of things to keep in mind. Number one, the Russian climate is incredibly erratic. And so just because they had a bumper crop this year doesn’t mean they’re can have a bumper crop next year.

Keep that in mind. Number two, the Russians have said that any vessels, civilian vessels anywhere in the Black Sea going anywhere near a Ukrainian coast, they reserve the right to attack. The Ukrainians are trying to convince people to come anyway and they’ve had very, very, very limited success. But that war risk is always there. And for their part, the Ukrainians have said and have demonstrated that they can strike Russian ports as far away as never seasick, which is their major green loading facility for the Russians.

Now, they have not gone after civilian vessels yet, but again, there’s still the possibility that we can have a widespread war on the water, in which case all civilian shipping in the north eastern half of the sea is in a degree of risk. So for the moment that there’s enough grain out there, I’d not get used to it.

But at the moment, that’s where we are. Okay. Talk to you later.