Read the other installments in this series:

The American Retreat, Part I: Oil

The American Retreat, Part II: Soldiers of Fortune

Not one to collect moss, Donald Trump shot directly from the G20 summit to South Korea July 1 where he nearly skipped the pro-forma niceties with the South Koreans for a tete-a-tete with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. Not only did the meeting happen in the DMZ itself, Trump became the first sitting American leader ever to cross into North Korean territory proper. The bulk of the talking heads in the American foreign policy community had a series of minor strokes at the sort of friendly PR Trump laid out for a guy who remains one of the most violently repressive leaders on the planet. They’ve got a point.

In (partial) contrast, I’m one of the people who was cautiously optimistic when the White House announced Trump would be meeting face-to-face with Kim both last year and this week. My feelings are less because I had high confidence in Trump personally or the new approach of engagement in general, and more because nothing else in the past seventy years had worked so why not try something new?

There were two things about the American-NorK summit that caught my eye.

First, personnel.

Trump is a bit hard on his staff. He’s impulsive, rude, belittling, and he becomes supremely bored and more than a bit aggroed when folks start presenting him with… information. He particularly loathes the sorts of details that accompany a contextual briefing. (I’m certain he would despise my work, for example.)

His cabinet, therefore, tends to fall into four general buckets. First, the blindingly incompetent (think HUD Secretary Ben Carson). Second, the sycophants (think Secretary of State Mike Pompeo). Third, those in charge of departments Trump just doesn’t care about (think Education Secretary Betsy DeVos). And fourth, those precious few who know how to say just the right thing to their boss so he gives them real leeway on real issues.

Of this last category only two staffers remain. The first is U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer. This newsletter is about harder security issues than are on Lighthizer’s remit, but if you’d like a bit of refresher you can review my thoughts on the current USTR here and here.

The second is National Security Advisor John Bolton.

When I read about how many people dislike John Bolton, I’m reminded a bit about Ronald Reagan – even those who hated Reagan’s policies admitted Reagan was pretty damned effective at getting his way. John Bolton is capable and competent in that vein and he lives and breathes all things foreign policy. Which most certainly does not mean he is an easy man to work with. Most who have had the dubious pleasure would never call him a prick because that would insult pricks everywhere. He is brash, aggressive, rude, and has little regard for things like diplomacy, tradition, alliances, institutions, or human rights. (Which come to think of it, is probably why he’s lasted as long on TeamTrump as he has.)

Two of Bolton’s pet projects are that he believes the Iranian and North Korean governments should be overthrown, preferably by force. And as the National Security Advisor he has the ability to shout that into Trump’s face (Bolton’s not the ear-whispering type) at every opportunity.

He’s had lots of opportunities of late.

Relations with Iran have been getting steadily sharper for months, what with the Americans laying on the sanctions thick while the Iranians have once again spun-up their nuclear program. Similarly, relations with North Korea aren’t exactly peachy, what with the North Koreans continuing to proceed with their own nuclear program in violation of clear American preferences. Bolton has repeatedly and forcefully advised Trump that the best counter to the Iranian and NorK positions involves ammunition.

Bolton has not gotten his way. A few days ago the Iranians shot down a large American surveillance drone. Bolton led the charge within the administration to retaliate with strikes on Iranian military facilities. Trump called off the strikes at the last minute.

But it is on North Korea that issues are proceeding in a new direction. Trump didn’t even let Bolton tag along to a summit with a foreign leader. Instead Trump sent Bolton off elsewhere.

It is one thing to overrule an advisor. After all, Trump is the president and it is his prerogative that matters, not Bolton’s. But to banish the only competent foreign policy hand in your administration to literally Mongolia (seriously folks, I cannot make this shit up!) is something entirely different.

’ve never been worried that Trump would start a war. Despite his trademark fire-breathing rhetoric, Trump has time and time again shown that upon reflection he’d rather de-escalate hostilities. But no matter what I feel about Bolton personally or professionally, I think it is an eminently good idea for at least one person in an administration to be able to locate Canada on a map. It appears Trump may be ushering out that one person.

The second issue is more… wishy washy, but has far grander implications than any mere personnel shift.

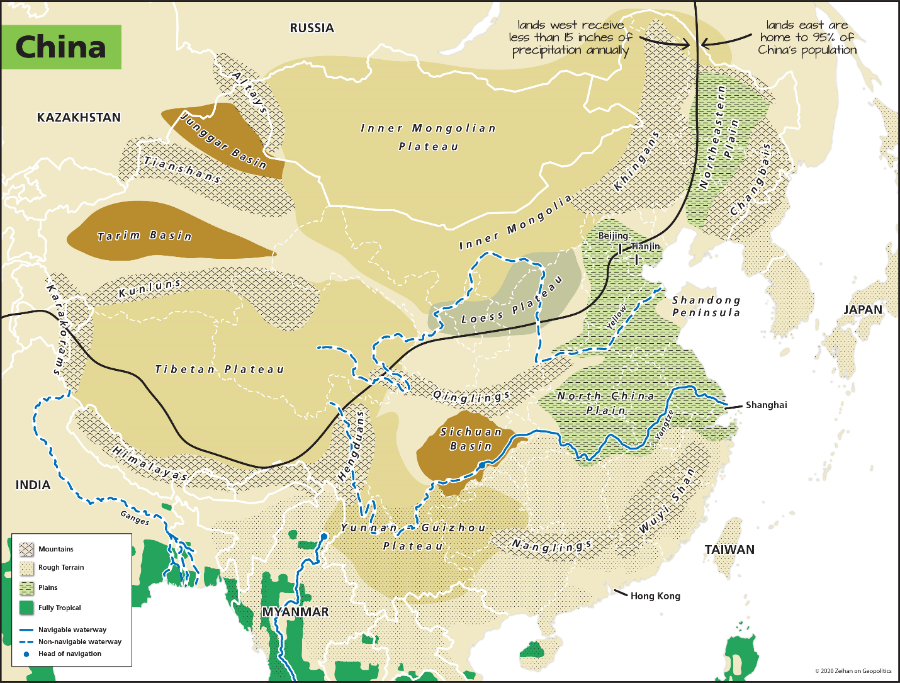

Even if Trump believes and trusts everything Kim says and Kim believes and trusts everything Trump says, the straight-up denuclearization of North Korea was never really on the table. North Korea lives in a tough neighborhood. Prickly (nuclear-armed) Russia to the north, nationalist (nuclear-armed) China to the west. Resurging (nuclear-capable-in-a-long-weekend) Japan to the east. And anxious (nuclear-capable-in-a-month) South Korea to the south. For the North Koreans these days, the American strategic preferences as regards the Korean Peninsula isn’t much more than a supportive footnote further justifying a program already viewed as core to national survival.

That seems to be reflected in Trump’s Korea policy. If the Americans are to step back from the world writ large, it is impossible for them to continue keeping the five-way strategic competition among Taiwan, China, South Korea, North Korea and Japan locked in ice much longer. There is something to be said for establishing a regional balance of power …and then simply leaving. To that end the handshake “deal” struck at the first Trump-Kim summit last year appeared to be that North Korea could keep their nukes so long as they forgo the developing of an intercontinental missile system. Put bluntly, North Korea’s nuclear program was being drop-kicked from being America’s problem to North Korea’s neighbors’. Kind of a dick move, but hey, geopolitics isn’t often about hand-holding.

The problem with this strategy – and the reason I’m hesitant to put my personal stamp of approval on it – is what happens next? Any Korean Peninsula without active American involvement is one in which the South Koreans have no choice but to go nuclear (just as any East Asia without American involvement is one in which both the Japanese and Taiwanese have no choice but to go nuclear.)

The American retreat will unlock a series of regional grievances that have been on hold for decades, but with the technologies of the now. An Asia without America is going to be a bit of a free-for-all, but that doesn’t mean someone won’t emerge on top.

My bet is entirely on Japan. The Japanese economy is the only one (aside from North Korea) that is not dependent upon international stability for its functioning. Put simply, everyone in Asia faces challenges as the world’s economic and strategic norms disintegrate, but for Northeast Asia, Japan’s challenges are the least extreme and Japan’s capabilities are the most advanced.

Fast forward less than a decade and Japan emerges from the post-Order maelstrom as Asia’s first power.

At that point Japan will not only have broken Chinese power, but will have massively added to what is already the world’s second-most capable expeditionary navy andit will be nuclear armed. A future America-Japanese dust-up is not inevitable, but history (strongly) suggests the future’s two most powerful naval forces will stumble across a few spots in the Greater Pacific where they rub each other the wrong way.

I’m fully willing to admit that the current East Asian balance of power is far from sustainable, but that hardly means I’m looking forward a Japanese-Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere with a nuclear chaser.