Read the other installments in this series:

The American Retreat, Part II: Soldiers of Fortune

The American Retreat, Part III: the Korean Peninsula

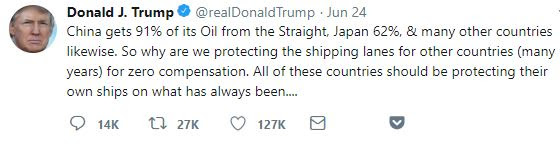

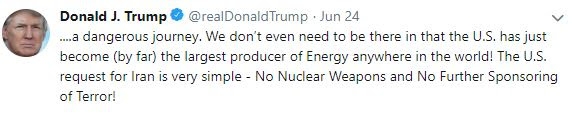

I’m going to do something I loathe and quote something I read on Twitter June 24. In a pair of posts U.S. President Donald Trump asserted:

Diction and statistical issues aside, these tweets comprise the 92 most important words used by anyone in the past three decades. Trump just made clear the days of America protecting global shipping – particularly of oil shipping in the Middle East – are over.

There is an easy argument to be made that the United States’ shale revolution will make the United States a net exporter of crude oil in the current calendar year, but to understand just how critical that is for the Americans we must first pick apart just how horrible that is for everyone else.

Let’s talk importance:

In the pre-Order world if you couldn’t obtain fossil fuels yourself, first coal and later oil, you failed to industrialize. Your manufacturing would at most be a step above cottage industries, so no mass education and no consumer goods (aka peasantry and mass poverty). Lack of fuel condemned you to having an at-best rudimentary transport system meaning your cities were very small, only able to exist in regions that could grow their own food (aka high living costs and low quality of life).

The handful of locations that could secure fossil fuels – either by producing it locally or by seizing it from others – could advance into something we today recognize to broadly mean “civilization,” which includes among other things homes that don’t leak and gadgets and full bellies.

This all changed in the late 1940s. After World War II the Americans created a global Order – a mix of security and trade guarantees which they used as a bribe to induce others to join their side in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. With global security now a thing, oil could be shipped safely and at volume without military escort, meaning that countries that didn’t have a military capable of escorting could now access fossil fuels. BAM! Civilization goes global.

Remove the Order, remove global oil markets, and civilization itself goes into screaming reverse in any location that lacks either the ability to produce oil locally, or the ability to venture forth and secure someone else’s.

Let’s talk vulnerability:

Crude tankers are huge. A modern supertanker can shuttle around oil weighing more than four Nimitz-class aircraft carriers. They are so big expressly because of the Order.

Pre-Order, merchant shipping used small, fast vessels because they needed to be able to scatter and hopefully outrun predators whether those predators wore eyepatches or naval uniforms. The Order ended such predation under the watchful eye of the U.S. Navy. Instead of commercial advantage coming as a result of speed and distributed risk, it instead came from efficiencies and economies of scale. Ships evolved to became slower to save on fuel costs, and bigger to get more bang for the buck. Today’s oil tankers are the slowest and biggest of them all and are nearly 50 times the size of some of the biggest cargo ships of the WWII era.

A similar logic holds with ports: size generates economies of scale. In addition, as ships have gotten larger, ports had to expand to match – a city with a small dock simply cannot handle a ship that is longer than the Empire State building is tall. Bigger, slower ships forced fewer, larger ports. Disrupt anything within the system and the damage quickly becomes extreme.

Between oil’s criticality to and ubiquitousness in modern life, oil is by far the most commonly traded product on Earth comprising some 18% of all maritime shipping traffic (by volume). About a third of all waterborne crude and product shipments originate in the Persian Gulf.

Let’s talk stickiness:

There are no shortages of politicians out there who agitate for relocating manufacturing capacity to their countries, provinces or cities. Making a speech is one thing, but actually building industrial plant and infrastructure is another. It costs billions and takes years for large industrial shifts, and even then there is no guarantee that a new industrial park will prove economically viable.

But at least manufacturing can be relocated. Commodity production cannot. Either you have it or you don’t, and the Persian Gulf has the greatest concentrations and volumes of easily-produced conventional crude oil on the planet. It can never not matter.

There’s also the impossibility of substitution.

Simply put, greentech isn’t ready. Most advances in greentech have to do with electricity generation, and since so few countries burn oil for electricity greentech’s impact upon oil markets has been negligible. As a rule greentech is shit for transport. High cost combined with insufficient energy density makes electric cars little more than a niche sector for early adopters, with Tesla’s recent sales figures crash indicating that market may already be saturated.

Even if the medium for most modern batteries – lithium – was sufficiently energy-dense to provide a viable long-term improvement in capacity (it isn’t), the stuff still needs to be mined and processed and fabricated into battery assemblies. Each step along the value-chain is so energy- and transport-intensive that very little of it can even be attempted without fossil-fuel-based energy for processing and transport across the world. As counterintuitive as it sounds, we need more carbon-heavy fuels to get to a lighter-carbon world. And that means coal and oil. A lot of oil.

There’s also the issue of lifespan. Most vehicles put on the roads since 1990 have a long lifespan to the point that even if every passenger vehicle sold from now on was an EV, we’d not see an end to oil in passenger transport for another two decades. Even then, even if every passenger vehicle and light truck were an EV right now, that would only make a dent in global oil demand. About 2/5ths of oil is used for transporting people and heating. The rest is much more difficult to do away with. Another 1/3rd is used for air transport, industry, and other modes that require far more range or power than electric engines can manage. And another 1/5th isn’t going anywhere ever, as it is what makes petrochemicals as varied as paints, plastics and pesticides possible.

(None of which means greentech won’t eventually solve the petroleum problem, but all of which means technology needs another couple decades to give it a go – and even that assumes the capital and educational structures around the world which have made the Digital Revolution possible hold steady at their current historical highs.)

Let’s talk protection:

At the end of World War II every nation of consequence aside from the United Kingdom had lost its navy. The United States in essence inherited the global ocean. America’s creation of the Order gave everyone aside from the Soviets a vested economic interest in not floating a new one. Fast forward to today and the American Navy is over ten times as powerful as the combined blue water fleets of every other country combined. Putting that force disconnect at the service of the global commons is what makes the Order work, and what makes global energy shipments and markets possible.

The world’s second- through sixth-most powerful navies in terms of long-range power projection are (roughly in order) Japan, the United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia. Of these only Russia need not sail forth for oil, as it has plenty of its own. France and the United Kingdom can secure what they need from the North Sea and North and West Africa. China has only 30 combat-capable surface ships of size that can effectively operate over 1000 miles from shore; unfortunately (for the Chinese) Southern China is a cool 5800 or so miles distant from the Persian Gulf. Only India – keeper of the world’s seventh-strongest navy – is even remotely proximate.

End result? Today’s oil markets comprise the greatest concentration of risk in themost critical economic sector at the most vulnerable part of the global system and no one can do anything about it if the Americans leave.

And that’s just the beginning.

By the way, for more on oil’s role in a world without American strategic oversight, I’m happy to refer you to my 2016 book, The Absent Superpower: the Shale Revolution and a World Without America.