Between 2000 and 2012 I worked at a place called Stratfor, which specializes in geopolitical forecasting. As I was one of the few members of the staff who had experience working in more than one region of the world, I wore many hats – one of which was to serve as an as-needed energy analyst. In that role, I found myself diving into everything from the Brazilian pre-salt to pipelines in the former Soviet Union to European Commission electricity regulations to Chinese state firm expansion policies to Japanese supply chains. And every year from May to October one additional brick was dropped onto my plate: hurricane watch.

Oil is one of the few truly global markets out there. There may be many categories of crude oil, but most are broadly fungible (you can swap out one crude for a variety of others in a pinch). Furthermore, demand for oil is inelastic – meaning that you have to have it to participate in a modern economy. So when something blocks one flow from reaching the market, the entire world suffers not just a price increase, but a sharp one. Back in the 2000s, hurricanes regularly plowed through the Gulf of Mexico – at the time home to about one-third of U.S. oil and natural gas output. In 2005 alone over a dozen major storms hit. (BTW, by far the best place to get info on active hurricanes is Weather Underground).

Each such event required an analysis of the storm’s path in relation to energy infrastructure so that I could estimate how much production had to be taken offline as precautionary measures, and then gauge the storm’s strength vis-a-vis the subsea pipe network to guesstimate how long production would remain shut in. In many cases, output would not recover for over a year. Price increases in excess of $10 a barrel for oil and $1 a gallon for gasoline were par for the course.

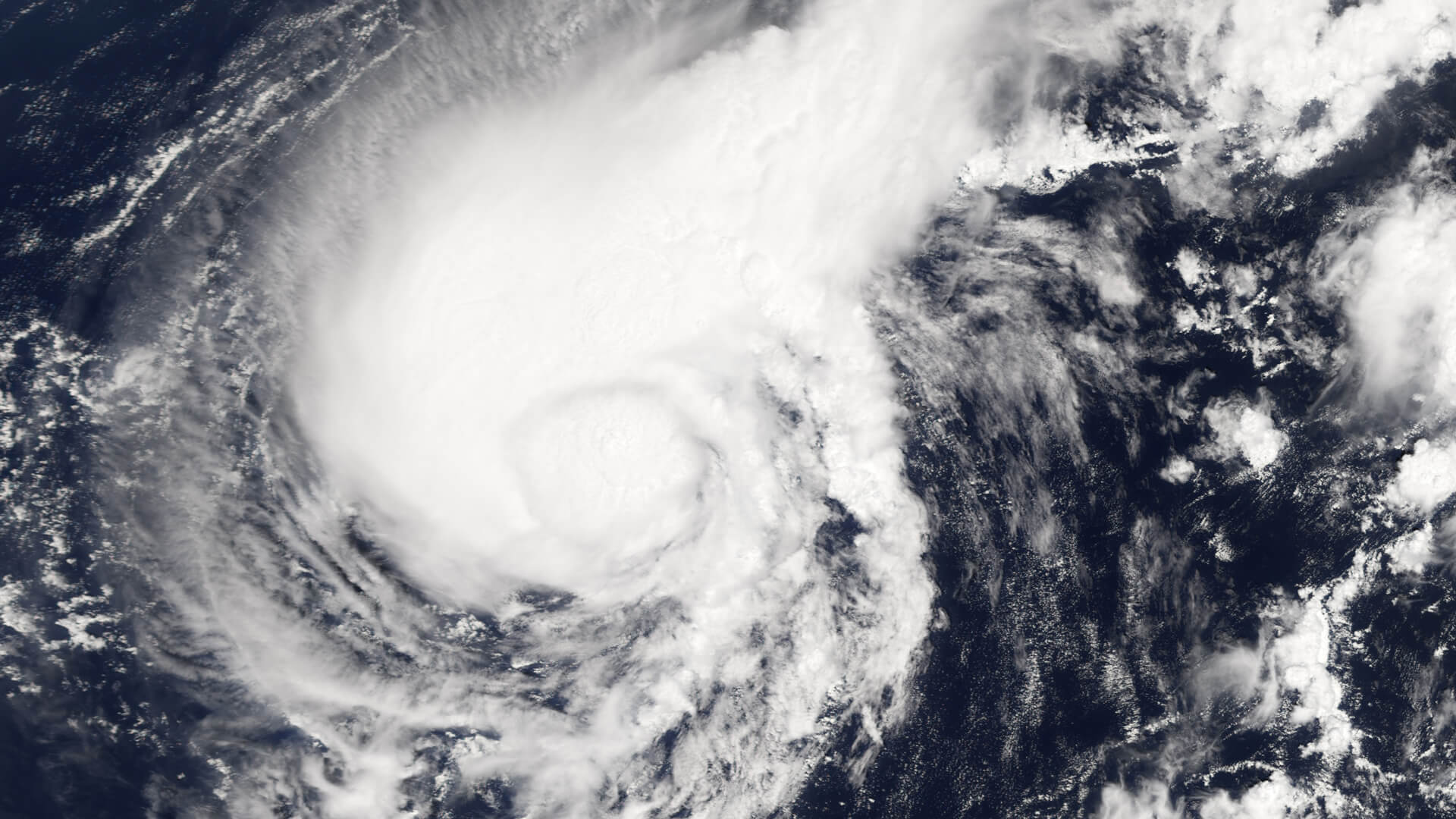

Hurricane Harvey is plowing through the Gulf of Mexico as I type. The storm is expected to edge into the Texas coast within the next 24 hours and then… just… sit… there. For at least three days. It is by far the worst-case scenario for the offshore energy industry. Not only does everything need to be shut-in, but the on-shore supporting infrastructure and staff will have to hunker down against 100+ mph winds for days. Damage assessments – much less repairs – will not be able to begin until at least Wednesday, and likely longer. The humanitarian impact looks dire: millions of coastal Texans will have to hold on for at least 72 hours before emergency services can begin to mitigate Harvey’s pummeling.

Harvey’s biggest economic impact will be on the various refining and petrochemical facilities that dot the Texas coast from Brownsville to Houston. It is the greatest concentration of such facilities in the world, and, at a stroke, supplies about one-third of American fuel needs. Rain that will be measured in feet as well as storm surges will flood much of the zone, and high winds will conspire with flat terrain to slow that excess waters’ draining back to the ocean. Energy prices will certainly rise in response.

But probably not by all that much.

Unlike the 2000s when a moderate storm or a glancing blow would reliably send oil prices skyrocketing, things are different in 2017. Part of it is that the U.S. hasn’t been hit by a meaningful storm in a decade, and so stockpiles of various fuels are at comfortable levels. But a far bigger factor at work is the shale industry. The shale sector didn’t exist in 2005, but now it accounts for most U.S. energy production. Every single shale well in the United States is on land, which means all the 9ish million barrels a day of shale oil output – some 70% of total U.S. output, just isn’t very vulnerable any longer. (In fact, Harvey is even providing an opportunity for the industry to test the theory that shale production is stormproof: Texas’ Eagleford shale play will get over a foot of rain.)

It isn’t just hurricanes that don’t much bother energy markets. It’s that, well, nothing much does.

We’ve been at $60 for a barrel of oil or below for three years now and things have not been quiet. Think of what’s happened of late: ISIS has taken over Iraq’s western desert, Iraq’s Kurds have achieved de facto independence, China is putting a naval base in Djibouti, Brazil’s entire political order is collapsing, Mexican oil output has cratered, net Southeast Asian energy exports have ceased, North Sea oil is in terminal decline, Venezuela is giving civilizational collapse the ole’ college try, Saudi Arabia and Iran are already fighting an eight front cold war and using a lot of bullets in doing so, Russia invaded Ukraine along one of its export pipeline routes resulting in Western sanctions on the entire Russian energy sector, Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un are trading nuclear annihilation threats. And yet oil prices just cannot get a lift.

So long as we are in this happy geopolitical moment where the global system still exists, shale has poured oil on troubled waters – providing one very welcome bit of calm in an increasingly-troubled world. But don’t get too comfortable.

It is all temporary.

As the retrenchment that the Americans began under Barack Obama accelerates under the Trump administration, the ability and willingness of the United States to hold the global center is fracturing. And soon, so will the global system as a whole. At that point, the United States will have a large, deep, stable energy market that is supplied from within the confines of North America. And the rest of the world will have to learn to deal with Iraq and Iran and Saudi Arabia and Russia and Ukraine and China and Indonesia and Venezuela and Brazil without any security arbiter. The result will be an energy crisis global in scope, except for the United States which will not participate. Expect the U.S. presidency and Congress to quickly (re)enact an oil export embargo to sever local oil markets from global oil markets. U.S. and Canadian prices will likely ceiling below $70, while everyone else will be lucky to have prices double that.

For more on how the American and global energy sectors will evolve and convulse in the years ahead, read The Absent Superpower: The Shale Revolution and a World Without America.